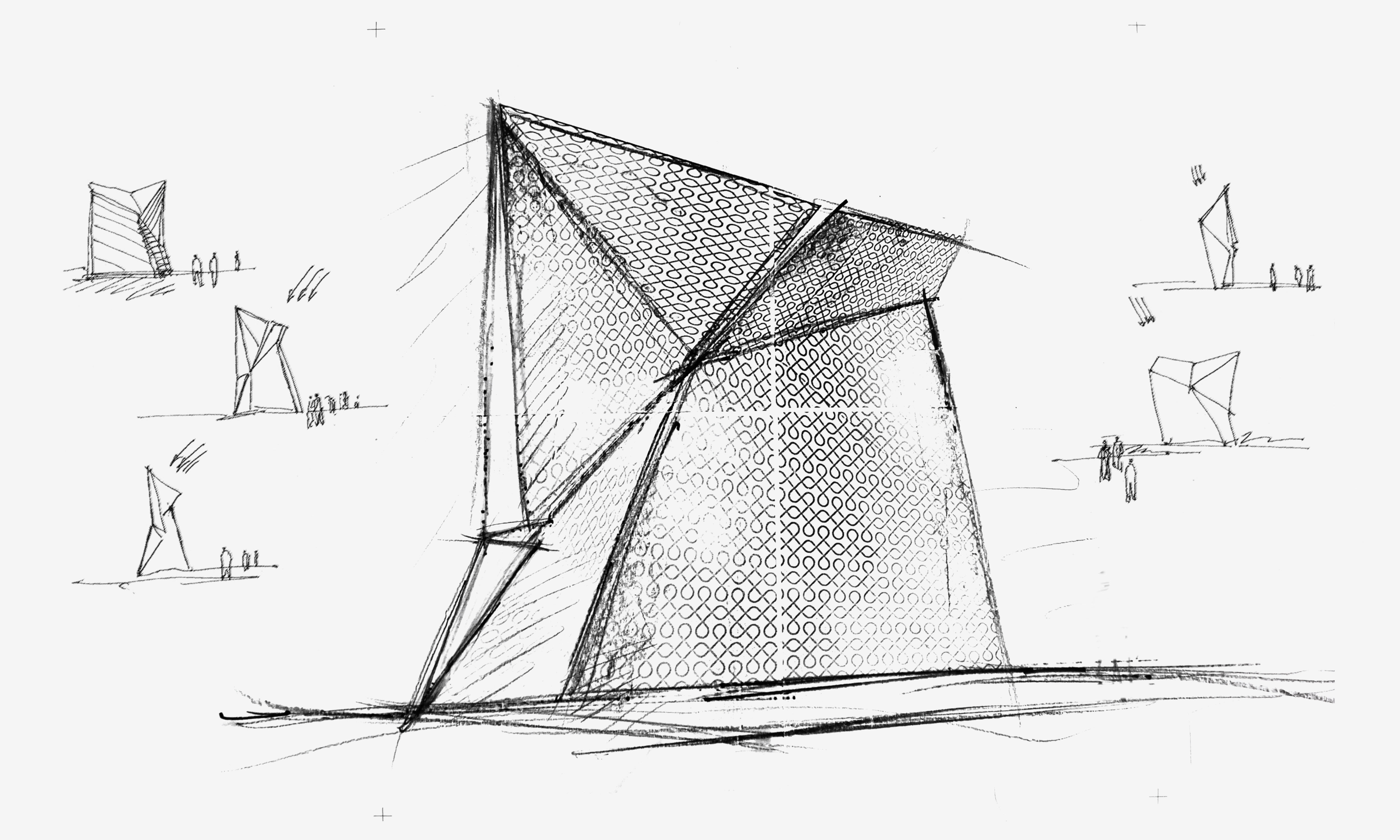

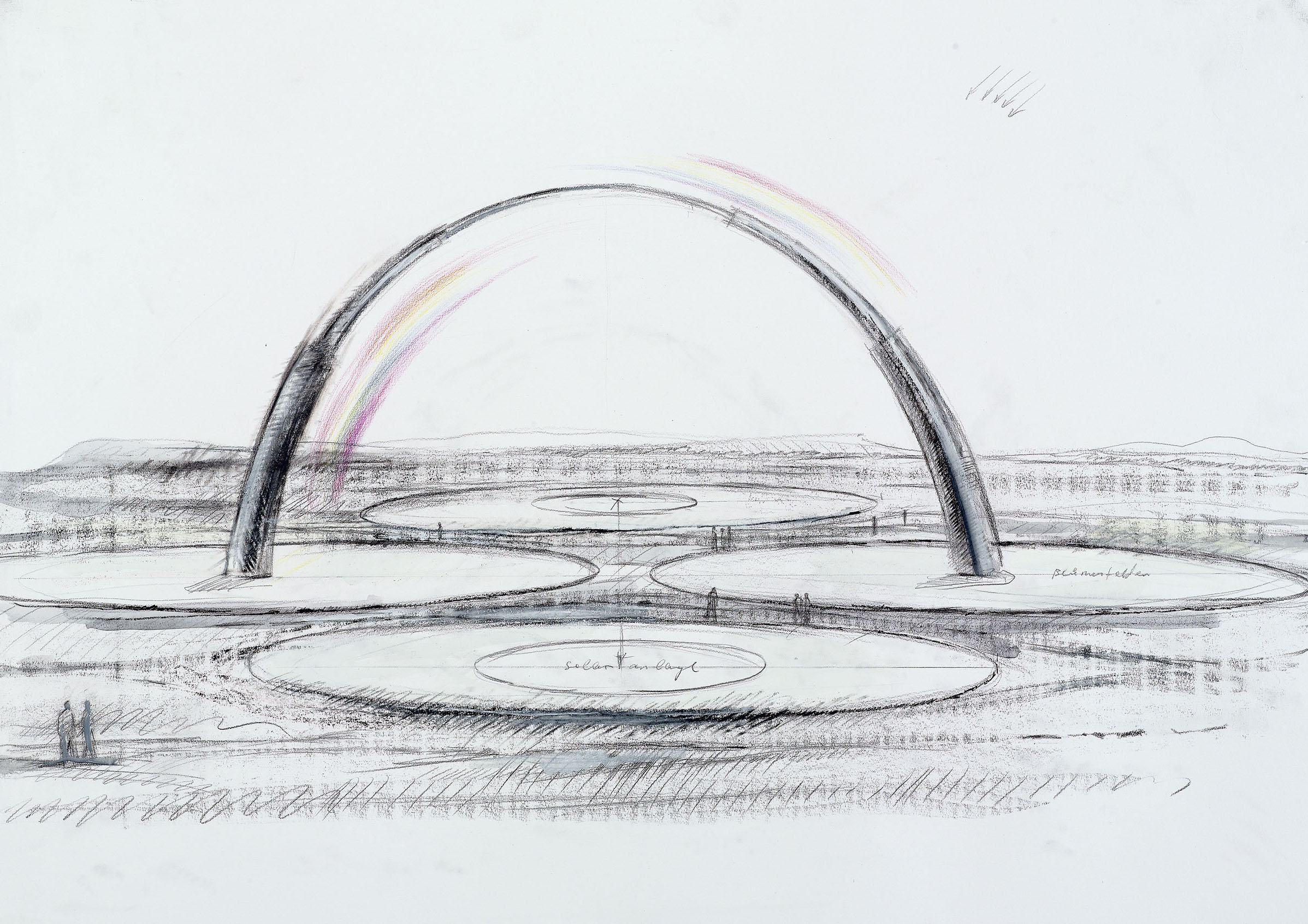

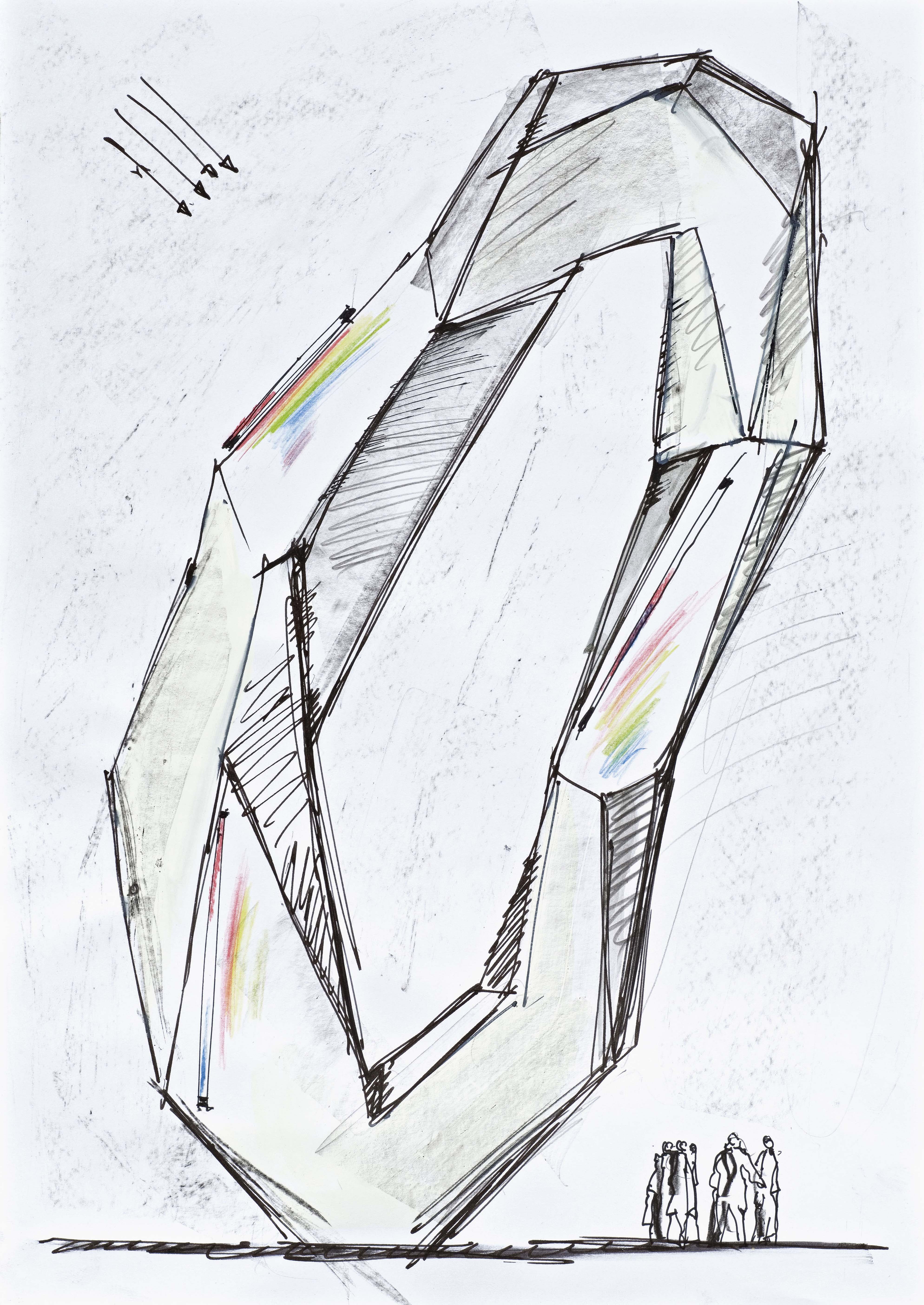

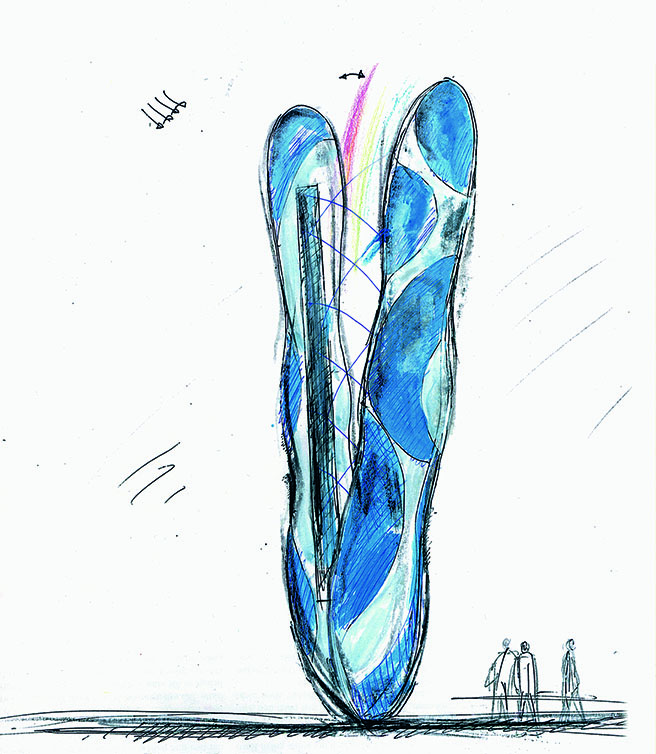

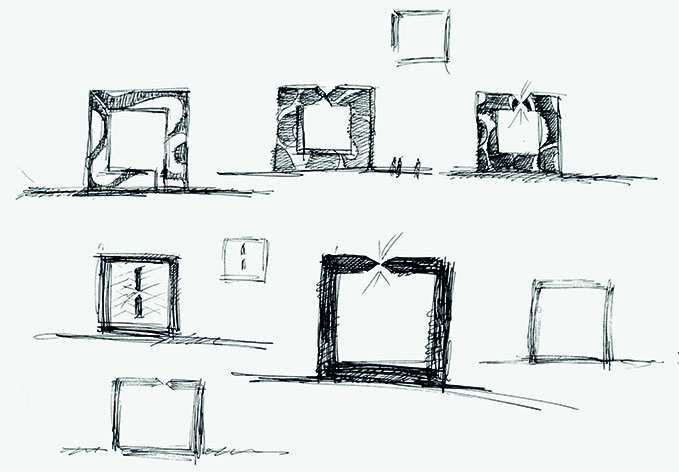

Vadim Kosmatschof works and constructs series of “solar sculptures” for public spaces in collaboration with the Vienna based multidisciplinary architectural studio Veech X Veech. Both aesthetically and technologically, these are groundbreaking works. They represent a constructive artistic ethos which, during the past forty years, was almost forgotten in Europe, but which, from the current perspective, presents tremendous new possibilities. The incorporation of advanced technology into these sculptures revives an old modernist ideal cultivated by Auguste Perret and Le Corbusier, the Bauhaus, and members of the early Soviet avant-garde such as Tatlin, Melnikov and Malevich, namely that a true artistic innovation must not only be an aesthetic innovation in the narrower field of art, but must also generate objective and universally recognizable progress in other fields, particularly in technology – and thus, ultimately, contribute to changing society. There is a real possibility that this very ambition, which the European society of the post-war period, absorbed in its hedonistic solipsism, lost touch with completely, may now, in combination with American optimism, galvanize the art world and remind it of its responsibility for the future.

What led to these enormous cultural differences between the builders of modernity in Europe, America and Russia? At the latest when Europe was divided after World War II, but basically beginning with the establishment of the Hitler and Stalin dictatorships, the modernist period came to an end. Whereas at the beginning of the 1930s one could still speak of a more or less homogeneous project which followed quite similar goals and styles in Paris, Berlin and Moscow, the disastrous political division of Europe cut off the channels of exchange which had flourished up to that time, forcing modernism to develop in separate directions from then on. It was only in the 1960s under Khrushchev that tentative contacts were resumed here and there. However, the full reconstitution of the global art world as we know it today was only achieved after a tedious reconstruction process that lasted for decades, in which the artists who carried on the Russian modernist tradition, as in earlier decades, had to endure reprisals and deprivations that until today have remained almost inconceivable for anyone living in the West.

Art production – under all conditions

Vadim Kosmatschof’s life and work, more than those of almost any other artist, exemplify important stages in this process. At the same time, Kosmatschof has revived the constructive tradition of modernism that was lost to the West from the 1930s onward, a lack which was a major factor in attenuating the concept of modernism here during the post-war reconstruction period. With the integration of contemporary Russian art into the global art world starting in the 1990s, not only did many new and unfamiliar positions enter the (Western) art debate, but it also became clear that the new ideas and markets in art had also initiated an unexpected surge of growth, which is still bringing universal benefit today.

Kosmatschof/Veech, with their Russian-American background (Stuart Veech is an American and runs the architectural firm Veech Media Architecture together with Mascha Veech, the daughter of Vadim Kosmatschof) and their locations in Vienna and Germany, are in an ideal situation in this regard. American enthusiasm, Central European “morale” and Russian constructive genius add up to a mixture of diverse abilities capable of producing powerful innovations at the interface of architecture and sculpture.

But how did Kosmatschof manage to build a solid basis for what was to become a “post-Soviet” oeuvre under the extremely difficult conditions that artists faced in the Soviet Union during the post-war years? Continuing to work on the development of modernism or even just continuing to develop art on the basis of artistic rather than political criteria demanded a tremendous amount of conviction, courage and resilience. Any objective information about art that an artist acquired had to be literally wrested from the rigid system around him, and every innovation he made could only be developed by means of subversive methods. An artist who produced non-conformist works could only survive on the sidelines, outside of the recognized Soviet art world: Kosmatschof was able to realize his first sculpture for a public space “only” in Turkmenistan, with the help of penal laborers. And Ilya Kabakov, the most internationally renowned artist of Kosmatschof’s generation, had to resort to commercial graphic art for a living in order to find time and freedom in which to work on his own art. The entire milieu of dissident and unofficial art in the late Soviet Union existed in a constant state of oscillation between enormous risks: the subjective risk of conforming too much to the prevailing conditions, and the objective risk of losing all possibility of production altogether. And even the nonconformist art itself, which these artists managed to create in the little bits of illicit freedom they were able to wrest from the Soviet regime, signified a risk, because, having no place in the official art world, they could expect no official reception of their works − and no change in their own difficult living and working conditions.

The heritage of the constructivists – a brief thaw from 1956 to 1964

Kosmatschof first studied painting for seven years at the Moscow Secondary Art School near the Tretyakov Gallery, which enabled him to glean his first impressions of the historical avant-garde in his teenage years: with an identification card from his school it was possible to view, in the basement storage rooms of the Tretyakov Gallery, works that were not publicly displayed upstairs – and the paintings of Chagall and Kandinsky became stamped into the artistic memory of the prospective young painter. In the storage area of the Pushkin Museum and in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg (then Leningrad) one could see large series of pictures by Henri Matisse, which had been bought up by the textile industrialist Shchukin in Paris before the Russian Revolution. At the end of the 1950s there began what the younger generation of artists saw as a kind of “golden era”: Commencing with Nikita Khrushchev’s assumption of office in 1955, foreign influences were tolerated for the first time in decades. In 1956, the Pushkin Museum presented a sensational Picasso exhibition, which officially inaugurated the brief so-called “Thaw” that lasted until 1963.

After secondary school, Kosmatschof studied from1959 to 1965 at the Stroganov School of Industrial and Applied Art in Moscow, which, like many similar institutions all over Europe, had been founded in the mid-19th century as a training workshop for designers, under the new conditions of the industrial age. Some of the professors who taught there in the 1960s had, in their youth, attended the VKhUTEMAS, the legendary “Artistic and Technological Workshops” where, from 1920 to 1927 (and from 1927 to 1930 under the name VKhUTEIN – “Artistic and Technological Institute”) almost all the artists of the Soviet avant-garde who are world-renowned today, including Rodchenko, Vesnin, Tatlin, Gabo, Melnikov and El Lissitzky, had taught. Kosmatschof’s painting professor Vassiliev, his material science professor Korshu, and the furniture designer and director of the school, Bikov, all came from the VKhUTEMAS. Around 1960, they were still not officially permitted to promote the positions of the former Soviet avant-garde, but they created a climate in which students were able to approach classical modernism to a certain extent – at least for those who wished to do so; the others aspired to careers that were in conformity with the system. Apart from this, the Stroganov School offered high-quality technical training in the best Russian tradition, with a particular emphasis on building construction. This central focus, which had been established at the time of the construction of the railway in the 19th century, had been a basic principle behind the constructive ambitions of the Soviet avant-garde even before World War II: Naum Gabo postulated that an artist should be able to realize any form out of any material, rather than developing the form from the material.

During this short Thaw period under Khrushchev, a library for foreign literature was opened in Moscow. This library was accessible to students and provided the only official source of information about not only international, but also Russian art history. However, Kosmatschof, together with friends like Alexander Nay, who later also emigrated to the West, also studied Western art and literature in secret. In the six years that Kosmatschof spent at the Stroganov School, the students of the class in monumental sculpture were taught only how to produce architectural sculpture that was strictly in line with the prescribed architectonic modules of the construction industry, and monuments that complied with the restrictions of Soviet urban development. Kosmatschof, however, attracted attention with a provocative study project in which, in place of a mathematical parameter, he made the human being the “module” of architecture, thereby demasking the inhumanity of the Soviet system. In the less prominent departments of metalworking and ceramics, the students were at least sometimes allowed more freedom of design and were not exclusively forced to produce the figural art of Soviet realism. Nevertheless, Kosmatschof’s diploma project – a 30 m² wall relief – received a poor mark, because it was abstract instead of figural.

“Provocation” and repression

In 1962, while still studying at the Stroganov School, Kosmatschof began teaching art at a “People’s University”, a kind of open university for students from the distant provinces of the Soviet imperium; he taught at this institution until 1968. There he built up a collection of students’ works which demonstrated naïve painting of a high quality – unspoilt, as it were, by the Soviet system. In 1967 he presented an exhibition of works by some of these amateur artists, having deliberately searched the outlying provinces for works that had been rejected by local juries. This exhibition exposed him as a critic of the official art world, which brought him a rebuke from the political authorities.

Meanwhile, Kosmatschof’s own artistic career had begun. In 1967, one and a half years before he graduated from the Stroganov School, his diploma project, an abstract ceramic relief for a large building, was reproduced in the magazine DI (“Applied Art”) together with a portrait of the young artist and a positive critique. This attracted the attention of a young architect working under Mihail Kruglov in one of the state planning offices. Kruglov, like some of the professors at the Stroganov School, was a graduate of the former VKhUTEMAS and immediately recognized the quality and the secret roots of this work – which was subsequently realized on the facade of a cinema. Kruglov was highly cultured and he showed Kosmatschof his private art collection, which included copperplate engravings of Italian vedute. The cinema commission gave Kosmatschof a good start in the official sculpture and monument industry in the Soviet Union, which at that time was in full flower, as every city was in need of monuments to Lenin, Stalin and other heroes of Socialism. A “free” artist who was dependent on state workshops for the realization of his works could make a good living in this way. And Kosmatschof was particularly in demand, because he had studied both metalworking and ceramics – an unusual double qualification. At that time, artists who devoted themselves to the quasi “assembly-line” production of political monuments (the best of them could hand-fashion a bust of Lenin out of a lump of clay behind their backs within ten minutes) earned ten times as much as a regular laborer.

In 1971, Kosmatschof created a fountain figure for the Yugoslavian embassy. While looking for a suitable sculpture at the sculpture combine, the Yugoslavian architect who designed the building had seen, in addition to numerous figures of Lenin, abstract works by Kosmatschof, and was captivated by them. In 1972, Kosmatschof – who had already caused a commotion with his exhibition of naive painting in 1967 – once again came into conflict with the authorities because, after officially participating in a ceramics symposium in Soviet-dominated Czechoslovakia, he did not return directly to Moscow but took a side trip to Danzig. The result was that he was banned from any further journeys out of the country. Kosmatschof also became suspect in the artists’ association because, as the functionary responsible for the admission of new members, he regularly invited the “wrong” artists – meaning those who deviated from the party line – to join. In 1974 and 1975 he succeeded in having one of his designs realized as an abstract monument in a public space – but this was in far-away Ashkhabad in Turkmenistan, in front of the National Library there, a fairly reputable building with late Corbusian characteristics. The official sculpture combines were not available for the realization of the twenty-meter-high steel sculpture, which was why Kosmatschof resorted to the laborers of a penal colony, who had considerable technical know-how. He lived and worked with them for eight months. During this period he also cultivated contacts with the West – in 1974, for example, he maintained contact with Hans Marte, the later Director General of the Austrian National Library, who at that time was employed at the Austrian embassy in Moscow.

Kosmatschof was soon made to feel the consequences of this new provocation on his part (after his exhibition of naive painting and his detour to Danzig): When in 1976, commissioned by the architect Felix Novakov, he designed four sculptures in yellow, blue and white porcelain for the Soviet embassy in Mauritania, he was not permitted to travel to the site for the assembly of the elements. Kosmatschof had to report to the ministry of foreign affairs for an interview with the KGB, who ordered him to hand over the assembly plans – which he refused to do. This resulted, in 1977, in Kosmatschof’s being banned from his profession, which also meant that he had to give up the studio to which he had been entitled as a member of the artists’ association. Kosmatschof submitted an application for emigration, which required an invitation from a foreign country. Kosmatschof’s old friend Alexander Nay, who, after undergoing forced psychiatric treatment seven times, had emigrated to New York, provided this invitation. The authorities, however, refused to accept the document and demanded that Kosmatschof submit an invitation from Israel – which, since he was not Jewish, was a pure case of harassment. When, by means of circuitous channels, he was finally able to present the Israeli invitation, his application was again rejected, whereupon Kosmatschof wrote an open letter to Soviet Party Leader Brezhnev, in which he described the absurdity of his situation. The famous dissident and philosopher Alexander Zinoviev, who lived in Munich from 1978 to 1999, passed on this letter to the German radio station Radiosender Deutsch Welle, which broadcast its contents. Three months later, Kosmatschof finally received permission to leave the country, and he emigrated to Vienna, arriving in December of 1979. Since then he has lived and worked in Germany and Austria.

Constructivism today

Today, looking back on the various factors that influenced his work, Kosmatschof comes to the following conclusion: The cultural heritage of the post-war generation was no more than a pile of ruins, but he and his friends received – like Rembrandt’s Danaë – a “shower of gold”, a kind of spiritual gift that enabled them to put together the remaining available fragments of Russian modernism. This reconstruction work in archives and libraries gave the young artists a strong sense of the idealism and enthusiasm that had vitalized their avant-garde predecessors in the 1920s, and these energies were transmitted to Kosmatschof. For a long time now, the question of seeking new forms on this historical basis has been the central focus of his deliberations, which, as a logical consequence, have always led him to the latest technologies, such as those he now employs in his solar sculptures.

The connection of the Soviet avant-garde with European object art today also implicitly poses the question as to which fragments of the constructive tradition in the West might also be part of this project. If we look at Kosmatschof’s sculptures of the past years, we can, in fact, see connections which show that his oeuvre is also rooted in non-Soviet discourse. From the monumental steel object “Konstrukta”, which Kosmatschof built in Ashkhabad in Turkmenistan in 1974/1975, to the designs and realized projects of today, which are presented in this publication, there has been a line of development that has brought several shifts in style as well as in content.

In “Konstrukta”, Kosmatschof’s method of operation was still very close to the role models of the early Soviet avant-garde. If we recall the fragile, apparatus-like objects of Alexander Rodchenko (for example the “space constructions” of 1918–1920, which were exhibited in 2006 at the MAK in Vienna), or works by Vladimir Tatlin, El Lissitzky or Georgii and Vladimir Stenberg (who, like Kosmatschof, had studied at the Stroganov School), the analogies are obvious: the artistic program consists in the design and construction of an abstract spatial composition which in content replaces the old figural and organic narrative with an optimistic, upwards-striving, future-welcoming enthusiasm for technology, and in material and gesture pursues a steely, puristic, space-activating rhetoric. Almost all the artists of Russian constructivism share this program as regards content and style, and it can still be seen almost unchanged in the vertical steel tubes and horizontally projecting surfaces and slats of Kosmatschof’s “Konstrukta” (as well as in the title of the work).

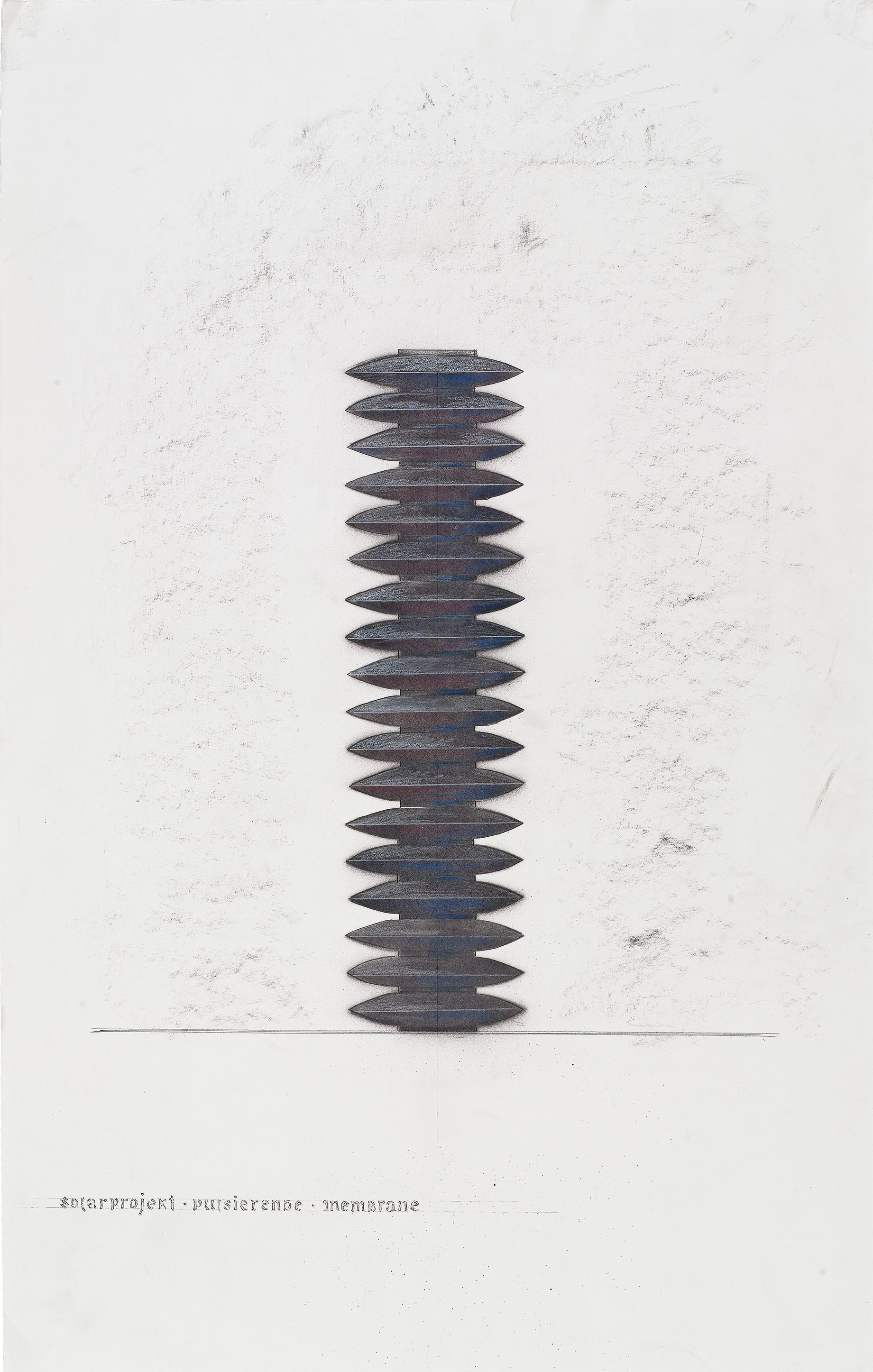

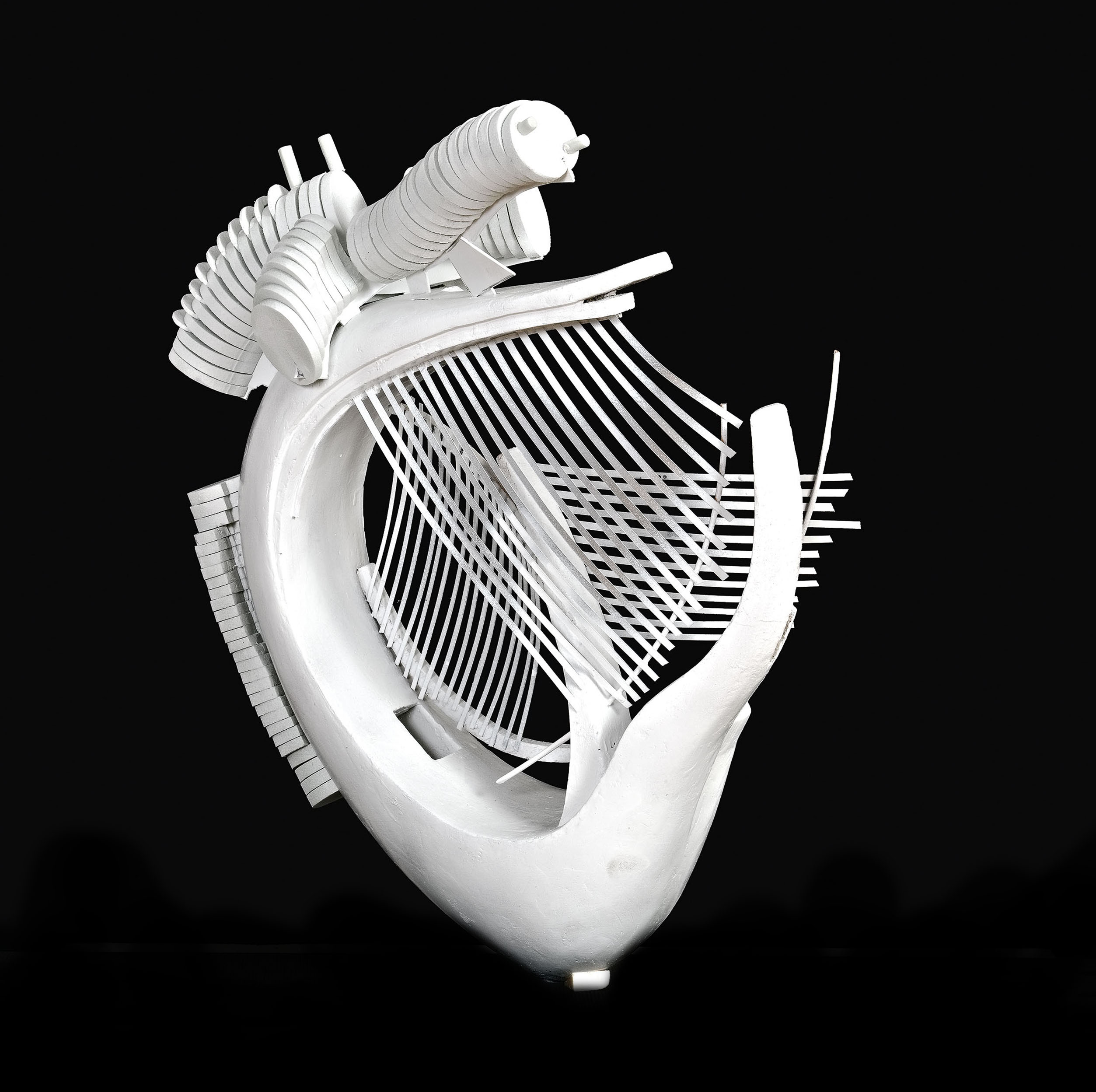

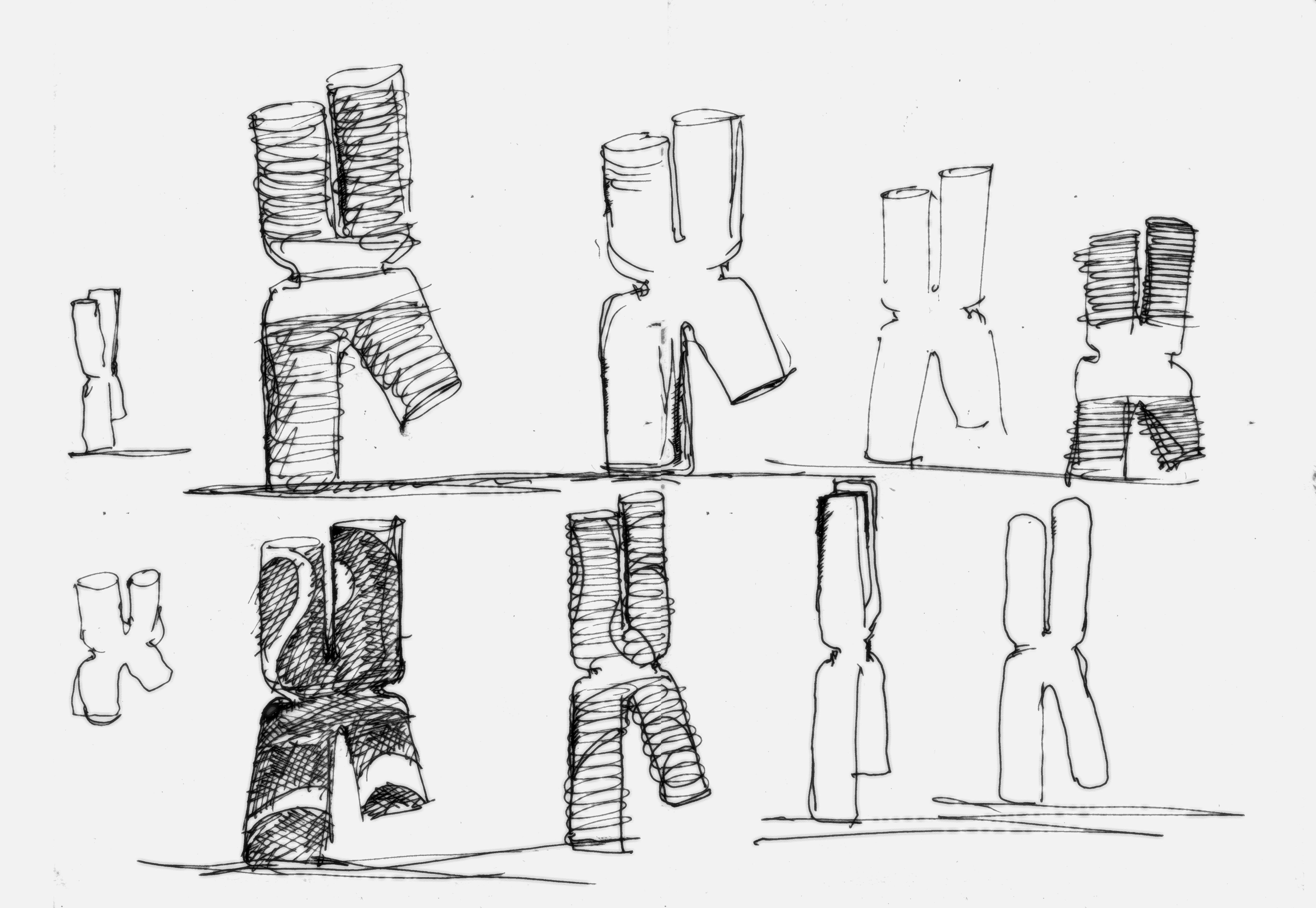

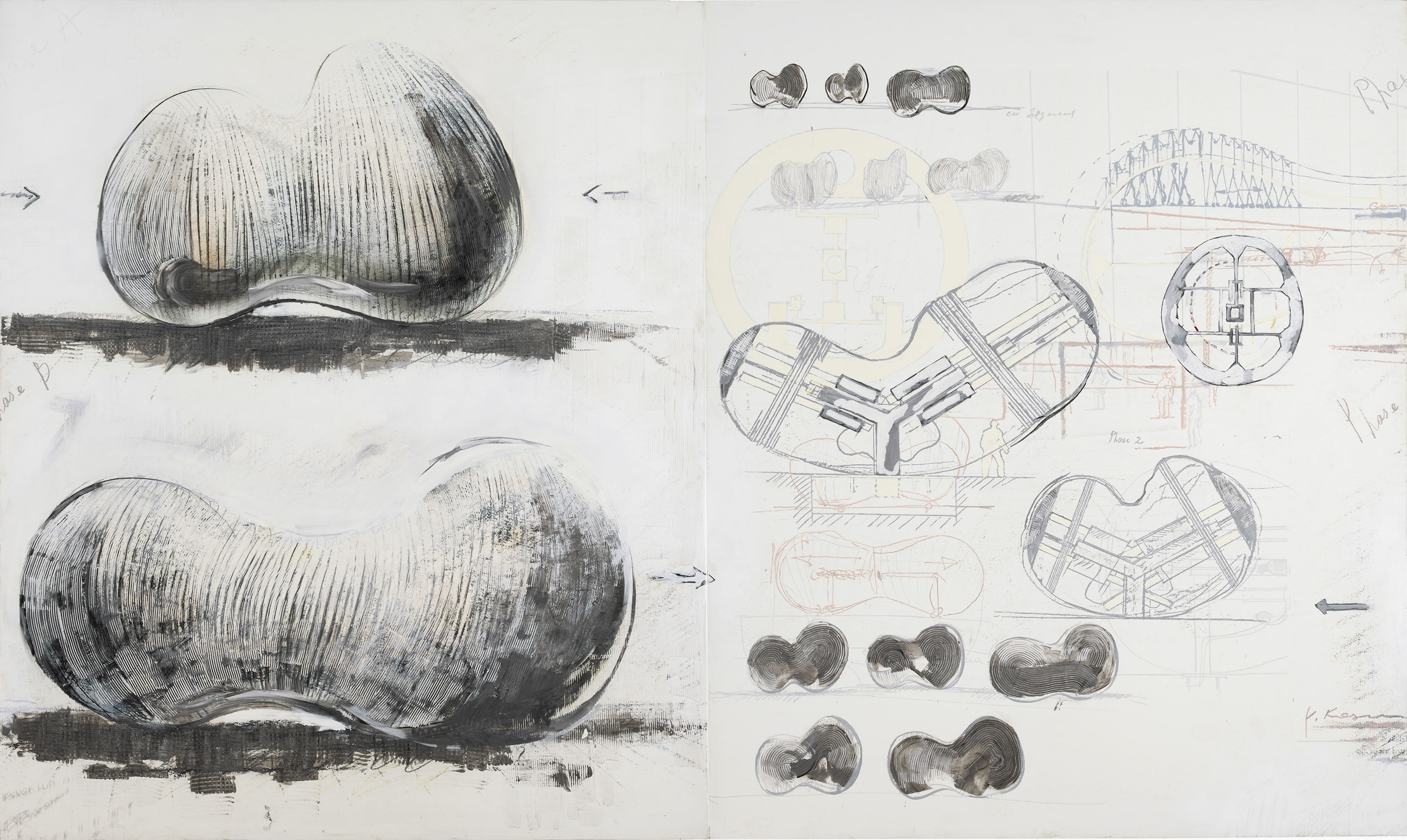

Kosmatschof’s current objects, on the other hand, are stylistically associated with organic (“Vertical Impulse” / “Vertical Fountain”, Breathing Form”) and partly even with realistic forms (“Urban Heart”), and their designs incorporate considerably more complex technology than the comparatively antiquated steel sculpture in Ashkhabad. What does this mean? Has the early constructivist experiment lost some of its impact? Is it simply out of date? Quite the contrary. The old ideals of constructivism are still clearly recognizable today: the basic optimism, the use of newest technologies as a matter of course, the positive attitude toward the powers of nature (perhaps in contrast to the irrational activities of human beings) and the taking for granted that these positions must be displayed in public spaces – all this is still reminiscent of the euphoric spirit of imminent change which imbued Russian artists right after the Revolution.

A hundred years later: the experiment goes on!

But in between lies the history of modern sculpture in the 20th century, which for long periods was molded by Western influences. In the first wave of modern sculpture that appeared shortly before and shortly after World War I, both in the West in the Bauhaus school, the futurists and the De Stijl group, and in the East among the Russian constructivists, a certain constructive dominance was certainly unmistakable. But in the 1930s, the traditions of East and West began to develop in different directions, and in the West, in addition to the old figural camp and the constructive camp of modern sculpture, an organoid, surreal one soon emerged, as manifested in the works of Marcel Duchamp, Jacques Lipschitz, Hans Arp, Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Henry Moore and many others. In the post-war period, these developments branched out into a variety of more highly differentiated movements: “informal” sculpture integrated principles of chance and the culture of everyday materials into modern plastic art, New Realism brought process-oriented positions, and the “social sculpture” of Joseph Beuys and Viennese actionism gave expression to social criticism. From the USA came the new minimalist movement, a key event of which was the “Primary Structures” exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1966, and land art radically broadened the canon of contemporary object art.

That did this mean for a Russian object artist who came to the (Central European) West in 1979 and was confronted, first of all, with remainders of pop art, with New Realism, with actionism and social sculpture? The most important adjustment he had to make concerned the relationship of the artist to society. Whereas in the Soviet Union, the regime made it virtually impossible for an artist to initiate any kind of communication with his clientele, namely the beholders of sculptures in public spaces and museums, thus nipping any kind of effect on society in the bud, in the West the exact opposite was the case. Starting in 1968 if not earlier, art was forced to take a stand on social issues, particularly art in public spaces, where it had to hold its own in the midst of a plurality of opinions and wishes. If we consider the fact that the early Soviet avant-garde was also explicitly sociopolitical in its outlook (a new art for new people through new technology), an unexpected congruency of opinion emerges regarding the role of art in society: there is no doubt that what Kosmatschof (also) valued in the early Soviet avant-garde was once again in demand in the 1980s and 1990s in the West.

In looking at the universal theme of natural resources whose potential can be demonstrated in technologically charged artistic installations, we can see a connection between the present day and the historical avant-garde – despite the hundred-year history of modernism that lies in between. Kosmatschof’s collaboration with the architectural firm Veech Media Architecture in designing and planning these new solar sculptures represents an interdisciplinary cooperation between art and technology that has a promising future. Thus it has been possible, at the beginning of the 21st century, to continue the experiment that, due to historical circumstances, so swiftly came to grief at the beginning of the 20th.

Download as PDF

Vision, Construction, Demonstration (English)

Vision, Konstruktion, Demonstration (Deutsch)